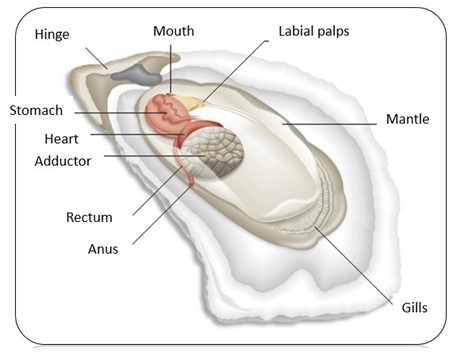

Oysters are unique and complex organisms with specialized anatomy that allows them to survive in dynamic marine environments. By examining the structure inside an oyster’s shell, we can better understand how these remarkable creatures function and thrive.

The Shell

The oyster’s shell is its primary defense against predators and environmental stress. Made mostly of calcium carbonate, the shell has two halves connected by a strong hinge. The outer layer, known as the periostracum, helps protect the shell from erosion and damage. The inner surface is lined with a smooth, iridescent layer called nacre, which provides additional protection and support.

The Mantle

The mantle is a soft tissue layer that lines the inside of the shell. It is responsible for producing and secreting calcium carbonate, enabling the oyster to grow and repair its shell. The mantle also plays a role in respiration and waste removal, ensuring the oyster maintains proper internal balance.

The Gills

Oysters possess specialized gills that serve two essential functions: respiration and filter feeding. As water passes through the gills, oxygen is absorbed, and microscopic food particles such as plankton are trapped in mucus and transported toward the oyster’s mouth.

The Mouth and Digestive System

The oyster’s mouth is located near its gills and is flanked by tiny, hair-like structures called palps. These palps help direct food particles toward the mouth while rejecting debris. Once ingested, food passes through the esophagus and into the stomach, where enzymes break it down. The nutrients are then absorbed in the digestive gland, while waste is expelled through the rectum.

The Heart and Circulatory System

Oysters have a simple heart that pumps colorless blood, known as hemolymph, throughout their body. This open circulatory system allows the hemolymph to flow freely over internal organs, delivering oxygen and nutrients while removing waste products.

The Adductor Muscle

The adductor muscle is a powerful structure that allows the oyster to tightly close its shell. This muscle is essential for protection against predators and environmental threats. The strength of the adductor muscle is what keeps oysters tightly sealed when shucked.

The Nervous System

Oysters have a decentralized nervous system consisting of paired ganglia, which are clusters of nerve cells that control movement and responses. While oysters lack a brain in the traditional sense, they can still respond to stimuli such as changes in light, temperature, and water conditions.

The Reproductive System

Oysters are capable of producing eggs or sperm, depending on their sex. Some oyster species are sequential hermaphrodites, meaning they can change sex during their lifetime. The reproductive organs release eggs or sperm directly into the water during spawning, where fertilization occurs externally.

Conclusion

Oysters are far more complex than they may appear at first glance. Their anatomy is highly specialized to support survival in fluctuating marine environments. By understanding the internal structure and functions of oysters, we gain deeper insight into their role in marine ecosystems and their value in aquaculture and coastal restoration.